Here comes the sun – Helios and Diwali at Kedleston Hall

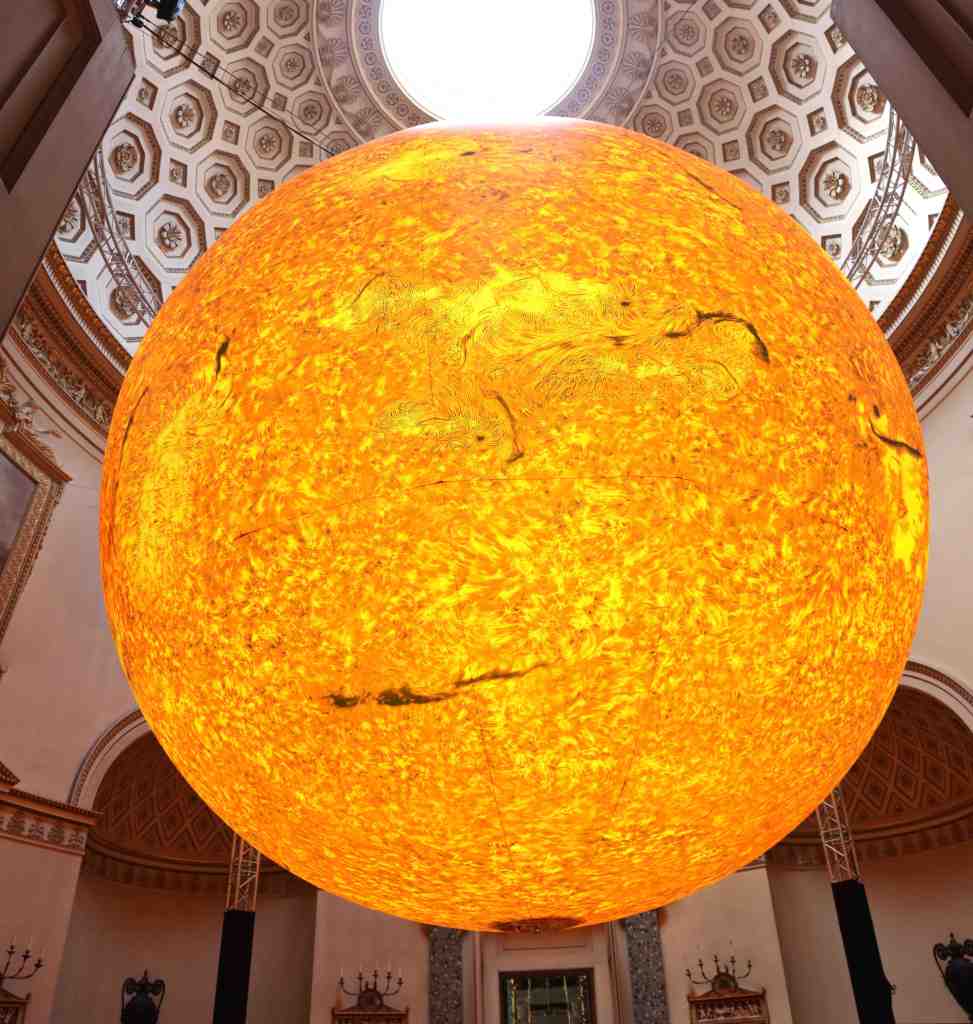

Last week we took a short trip to get up close and personal with the sun. Well not THE sun, obviously, but rather an art installation at nearby Kedleston Hall that portrays the surface of the sun in breathtaking detail, complete with sunspots and swirling solar winds. Helios is the work of artist Luke Jerram*, who based his creation on thousands of images of the sun collected by NASA and other astronomical organisations.

It’s easy to understand why Jerram was inspired to create Helios, which is named after the ancient Greek god of the sun. Did you know that our sun is 4.5 billion years old, and has about the same amount of time left until it runs out of gas? And it’s very, very hot! The surface of the sun is around 5,500°C, while its core has a mind boggling temperature of 15 million°C. Our sun has a diameter of 1.4 million kilometres (855,000 miles), but is just around average in size – some other stars are up to 100 times bigger. Wow!

Jerram’s brightly illuminated piece is 7 metres in diameter, and totally dominated the grand – 19 metres high – saloon hall in which it was suspended. The scale is mind-blowing, with one centimetre of the sculpture representing 2,000 kilometres of the real sun’s surface. Clearly, our sun is one really big dude. As if to make the point, displayed in an adjacent room and made to the same scale was a tiny model of the Earth. It really put us in our place; this planet, which to us seems impossibly huge, is a mere pimple when viewed from a cosmic perspective.

However, not everyone seemed convinced. Two other visitors, nerdy types – men, of course – were a bit agitated. They complained that although the representations of the Earth and the sun may have been made to the same scale, the distance between them had been miscalculated. According to their calculations, the model of the Earth should rightly have been positioned outside in the carpark, or maybe even half-way to the nearby city of Derby. I could barely stifle my yawns – why couldn’t they just appreciate Luke Jerram’s creativity, rather than droning on tediously about impenetrable mathematics? Life’s too short, guys!

Diwali Celebrations

Coinciding with the Helios exhibition at Kedleston Hall** was a celebration of Diwali, the Hindu festival of lights. This, I’m sure, was no coincidence. Diwali celebrates the victory of light over darkness, so programming an art installation with the sun at its very heart to run alongside a Diwali celebration was a stroke of genius.

This photo features Diwali decorations on the floor of the grand Marble Hall. Through the open door to the rear you can glimpse the lower part of Helios, suspended in the Saloon Hall.

This was the third consecutive year in which Kedleston has celebrated Diwali. Many Derby residents share a cultural heritage derived from the Indian sub-continent, and Diwali celebrations are therefore big in the city. Extending those celebrations a few miles north seems entirely appropriate, particularly in view of Kedleston’s historical links with India. Those links date back over a century to one of the stately home’s former owners – George Nathaniel Curzon, a.k.a. Lord Curzon (1859–1925) – who served as Viceroy of India between 1899 and 1905. Kedleston still displays many artefacts and artworks that Curzon brought back from his travels.

The Diwali celebrations introduced an unexpected splash of colour to Kedleston. At their heart were displays of hundreds of hand-crafted marigolds, which decorated several of the rooms. In Indian culture marigolds are used extensively in religious festivals, weddings and other ceremonies to symbolise purity, positivity and the divine, and they certainly brought a hint of the exotic to this traditionally English stately home. Other Diwali elements on display included clay oil lamps to light the way, and rangoli light projections.

Although fairly modest, Kedleston’s Diwali celebrations were good to see, and served as a potent reminder of the diverse population living within just a few miles of this grand building. I wonder what the old Viceroy would have made of them?

Remembering George Harrison

As we drove away from Kedleston Hall, having spent the afternoon in the company of the sun, and being inspired by the hope that is implicit in the Diwali festival, I found myself quietly singing a masterpiece by the late, sadly lamented George Harrison.

All four of the Beatles briefly embraced Indian culture following visits to that country in 1966 and 1968, but only George Harrison really got it. Much of George’s subsequent work was inspired directly or indirectly by Indian culture and religion, including I believe the wonderful “Here Comes the Sun” which appeared on the Beatles’ Abbey Road album in 1969. If you don’t know the song, or even if you do and would like to wallow in it one more time, listen to it here courtesy of YouTube.

* Postscript: Another work by Luke Jerram

A couple of years ago another work by Luke Jerram was exhibited at Derby Cathedral. On that occasion his chosen subject was the moon, suspended impressively above the nave. Clearly, he is fascinated by all things astronomical.

** Postscript: More on Kedleston Hall

My home county of Derbyshire is blessed with many grand stately homes. Kedleston is one of my favourites, and I have blogged about it before. You can read more about Kedleston Hall, and enjoy more of Mrs P’s photos, here and here.