Leighton House – spectacular home of a record-breaking lord!

During a recent trip to London our ambition to escape the familiar tourist treadmill led us to visit Leighton House, the former home of a prominent 19th century artist and lord of the realm. Frederic Leighton (1830-1896), the artist son of a Yorkshire doctor, was successful, well-travelled and wealthy, and in the mid-1860s he started work on a new house in the Holland Park area of the city. The result was spectacular.

The Arab Hall

Leighton’s intention was to build a house that would function as his artist’s studio, while also serving as a work of art in its own right. In so doing he was able to channel his creativity, to indulge his passions and to show off some of the more exotic items in his personal collection.

The Arab Hall

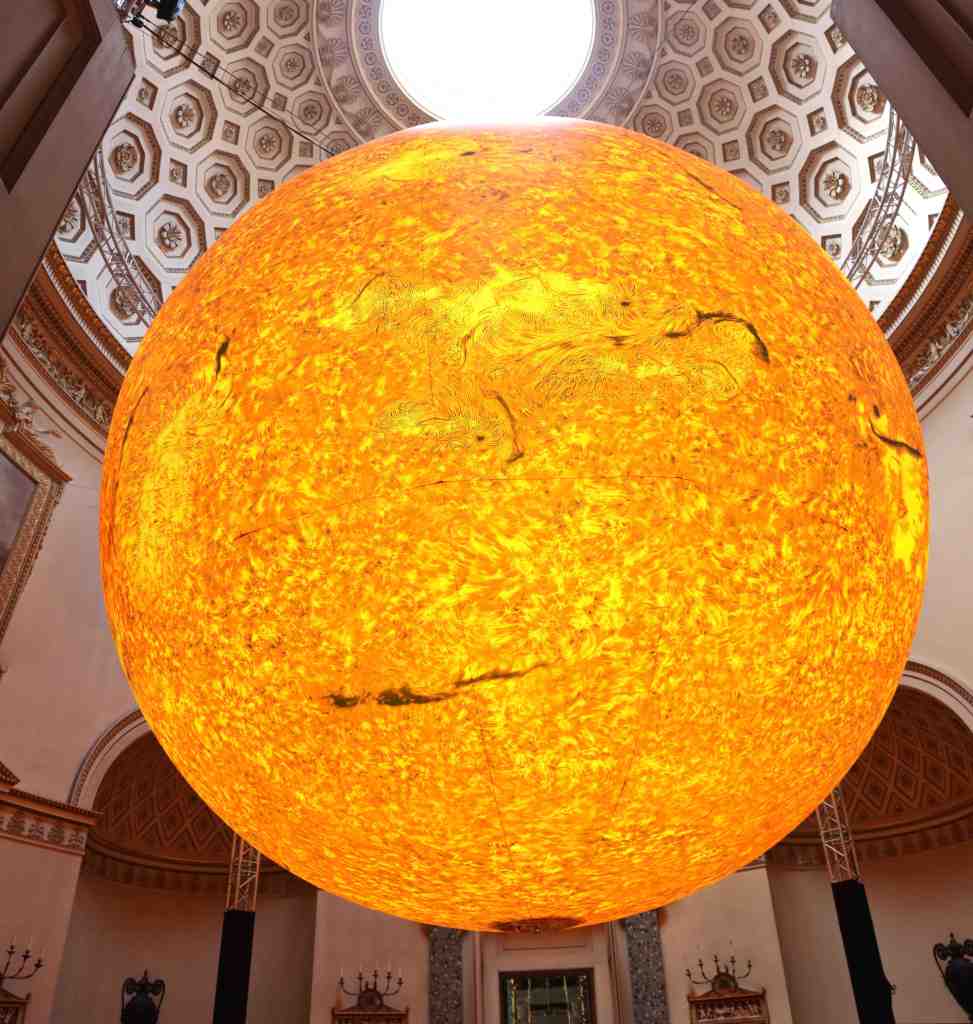

The undoubted star of the show at Leighton House is the Arab Hall, a space that was inspired by the architecture and gardens the artist had seen on his travels in North Africa, the Middle East and Sicily. The Arab Hall displays Leighton’s collection of tiles, most of which were made in Damascus between the late 16th and early 17th centuries, as well as works by contemporary artists he commissioned to help bring his vision to life.

The Arab Hall. In the bottom photo the Arab Hall is viewed from the Narcissus Hall. The statue is of Narcissus, who plainly fancies himself!

The Arab Hall was part of an extension added to the house in the 1870s. It was completed in 1882, and is said to have cost more than the whole of the original building. Money well spent, I think! Leighton is reported to have said of the Arab Hall that he wanted to create “something beautiful to look at”. Well, he succeeded, that’s for sure. It is simply stunning, all the more so for being so totally unlike anything you would ever expect to see in London.

Top Left: In the garden “A Moment of Peril”, a sculpture by Sir Thomas Brock created in 1881. Bottom Left: Rear view of Leighton House, from the garden. Right: View of Leighton House from the street; you would never guess what lurks within, would you?

Leighton was an eminent figure in the English arts scene in the latter half of the 19th century. He painted both portraits and landscapes, dabbled in sculpture and was a big player in the Aesthetic Movement, which championed “art for art’s sake,” prioritising beauty, sensuality, and visual pleasure over practical considerations.

The Silk Room was used to display paintings by artists who Leighton admired.

Frederic Leighton was highly respected in the artistic community, as demonstrated by the fact that in 1878 he became President of the Royal Academy of Arts, the prestigious, London-based institution that was founded in 1768 to promote visual arts through education and exhibitions.

Two paintings by Frederic Leighton.

Such was the esteem in which Leighton was held that on January 24th 1896 he was made a Lord, becoming Baron Leighton. It was a record-breaking elevation to the nobility as he was the first painter ever to have received a peerage. He probably felt pleased with himself, but sadly that did not last long. Just one day later, on 25 January 1896, Baron Leighton died, enabling Frederic to break another – and altogether more unwelcome record: nobody in the history of English nobility has ever held a peerage for less time than poor old Fred!

The Dining Room was mainly used for the display of pottery.

Baron Leighton therefore had no time in which build a reputation in the House of Lords as a formidable debater and champion of the arts. From that perspective he was – through no fault of his own, of course – a complete nonentity. But who really cares about that? The building of Leighton House, and particularly the creation of its Arab Hall, has secured Frederic, Baron Leighton’s legacy for all time.